First published in the Rural Weekly

I’ve seen a lot of changes happen in Birdsville over my lifetime. I remember starting school when I was 10 years old, much older than some of the other kids. That worked for me – I got to be the smart one in class, always getting asked to help with the little kids as they learned the basics.

I left in grade 5, and got my first job mustering cattle on horseback. Back then we didn’t have paddocks, or boundary fences, or even individual property lines. Cattle moved freely – we moved them on to each water hole when needed.

Life was pretty good back then. We didn’t need money, didn’t have cars, nor a mortgage or power bills. Each house was lit with a kerosene lamp, and we didn’t care about what we didn’t have. Working on the land, all we needed was a campfire for light and a swag to sleep in. What more could you want?

It’s funny thinking about how we used to enjoy the outdoors – especially the heat. It was no big deal to ride out into the landscape, with just a hat to shade your eyes. Living under the shade of tree as you watched over the cattle and looked up at the stars. Now I live in a nice house with air-conditioning, and every time I walk out I’m hit with the blast of the outback heat. Once you get used to modern comforts, it’s hard to go back.

Mustering with horses was a lot of fun – it kept you grounded to the land around you. Things move quicker these days – I see operations that need to move cattle in days, not weeks. Shifting stock into big road trains that power down the highways rather than moving slowly over the landscape.

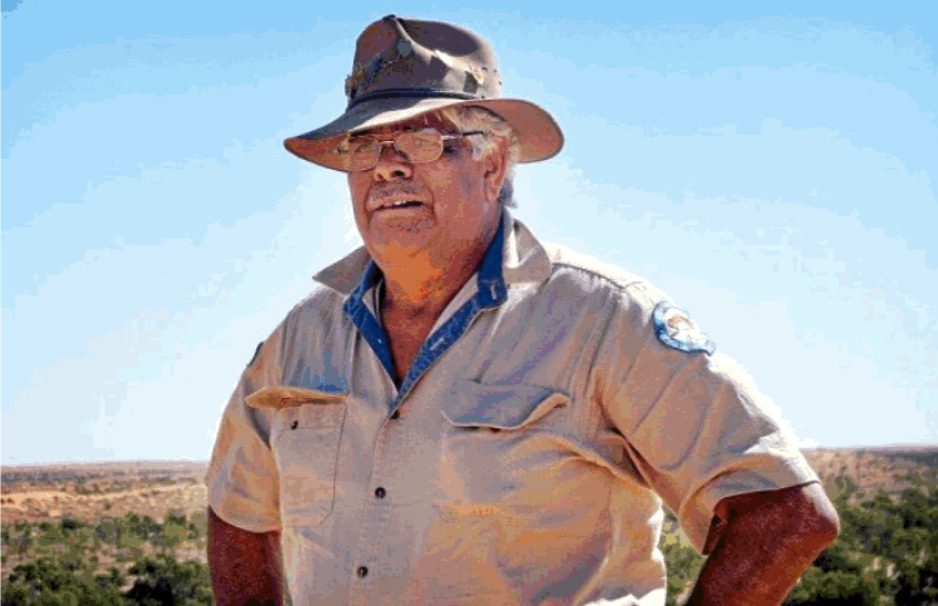

This land is unique, in every sense of the word. Over every rise, over every sand dune is a different view – of wildlife, rivers, mountains and valleys. It’s taking care of this land and ensuring it is protected that is a big part of my job today as a ranger for the Munga-Thirri national park. I was the first employee here – going on 25 years now – and it’s quite possibly the best job ever. I get to care for country that I’m a traditional custodian of – doing what I’m paid to do as well as my spiritual responsibility.

This job is an honour, and I often feel like I’ve won the Lotto to be able to do it. It gives me the chance to follow the songlines of my country – to look over it and ensure that the connection between land and people are kept alive. I often stumble across an old campsite, or a burial ground, or an old humpy, and those are the truly special moments. Seeing evidence of life that existed here hundreds, or even thousands of years ago. Seeing the history of my people in tangible artefacts like wooden or stone tools – blows your mind a bit.

I remember being taught the stories of my people when I was younger, and I’m honoured to be able to impart that on to the younger generations now. Every story tells a part of our history, but it’s more than that – it’s a map of how to travel from one place to another. Some of these places are physical, and some are not. That’s a fundamental thing to understand about how this land is part of my people, and we are part of it. It’s something that I love to share with others as they come visiting the park – to see their wonder as they enjoy the beautiful landscapes, wildlife and culture.

The old days of mustering and sleeping under the stars have more than a nostalgic importance to me – they are a lesson in how we need to work alongside this country, not work against it. With the passage of time, we need to preserve the old ways of looking after country – most importantly giving it the time to recover.

One thing that concerns me greatly is how we use water across this land. It’s such an important resource, and goes much deeper than the surface – literally and figuratively. It comes in the rains, runs through the rivers and the plains, and is stored deep underground. It’s a cycle that plays an important role in keeping this land alive and healthy. Our water is an important resource that needs to be managed sustainably.

It’s so important that we keep our rivers clean, and that has to be with an understanding of the relationship between native species and the land. I remember a time when native yabbies could be found up and down our river systems – now they’re struggling to survive in mud channels that are choked with introduced carp. Rivers stay healthy if we maintain the natural balance.

If we are to manage and sustain the health of this land, it’s important that we consider the heritage of that country. It’s been great to see progress on this over the years – from landholders, government and Aboriginal people working alongside each other. My job and those of other Indigenous Rangers are testament to that. The future of Australia depends on caring for our country.

Above all else, I’d like to see all of us who call the Outback home come together and work on a system that works for everyone – people, plants, animals and the land. We all care for this country in various ways – what is needed is a shared understanding of that care and a commitment to working together.

Don Rowlands is a Wangkangurru Elder and Indigenous Ranger of Munga-Thirri National Park in the Simpson Desert.